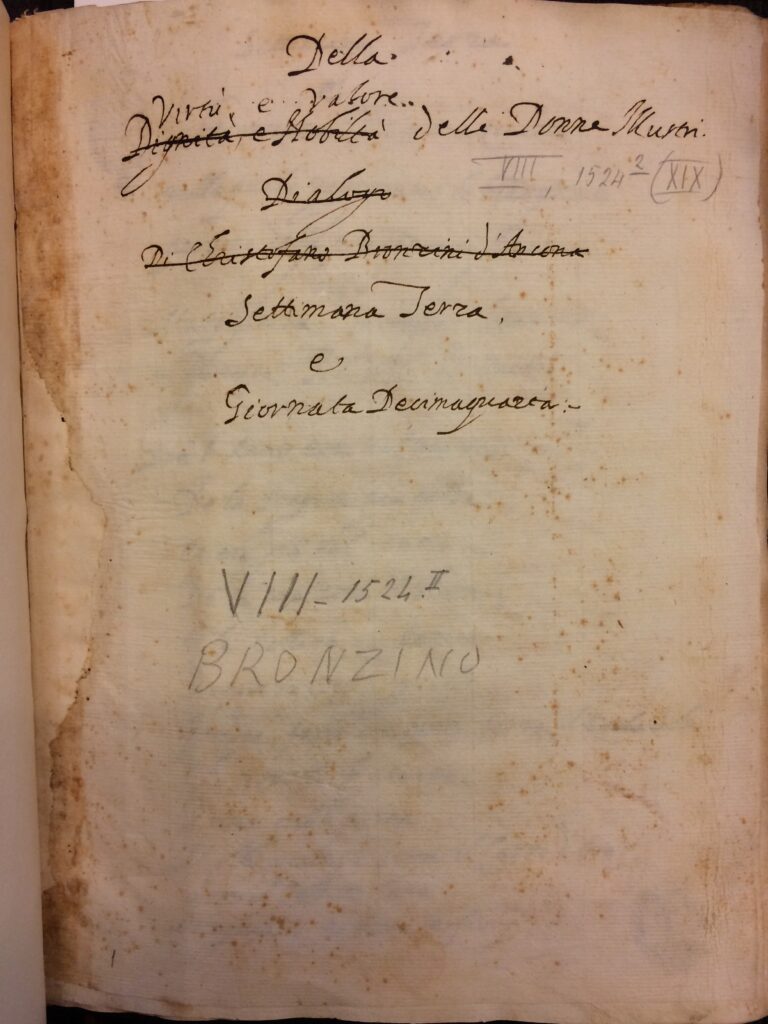

Thanks to a generous grant from the Colgan Foundation, the Medici Archive Project has embarked on a project to harness HTR technologies in order to give greater access to Cristofano Bronzini’s treatise entitled On the Dignity and Nobility of Women, an incomparable resource for recovering the history of women’s contributions to civilization, and for understanding the role of civic discourse in social change during the early modern period. Comprising 36 tomes, it was written in Florence and largely complete by the year 1622.

Bronzini’s titanic manuscript has been in the vault of the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale in Florence ever since the dispersion of the palace library of the Medici grand dukes, yet it was not recorded in any catalog until the 1980s. The aim of this treatise is to argue for women’s capacity to take part in the governing of the Tuscan Grand Duchy, at that time under Medici rule. It does so by mustering legends, histories, and first-hand accounts of thousands of female exemplars of nearly every virtue and every intellectual field, with a coverage from Antiquity to the writer’s own era that embraces all known parts of the inhabited world.

As a treatise dedicated to elevating women’s status in society, Bronzini’s On the Dignity and Nobility of Women can be connected with the so-called Querelle des Femmes (or, The Woman Question), a literary debate that transpired over centuries and that included such landmark texts as Boccaccio’s On Famous Women (1360), Christine de Pizan’s The Book of the City of Ladies (1405), and Moderata Fonte’s On the Worth of Women (1600). Interrogating the inborn nature of women and their place in society, the debate centered on such heated questions as whether girls and women should be educated, whether women could govern effectively, and whether women had ever made worthy contributions to society.

Cristofano Bronzini’s On the Dignity and Nobility of Women is the largest and most ambitiously encyclopedic text to have ever been written in the Querelle des Femmes tradition in any language and anywhere in the world, up to and including the present day. It is also the sole pro-woman treatise to have been censored by the Roman Inquisition, apparently due to one of its theses that argued women were more fit to govern than men, by divine design.

The value of Bronzini’s manuscript for recuperating the history of women up to the year 1622 is of the first order. Particularly invaluable are the treatise’s early ethnographic notices about women in civilizations around the world, including Egypt, China, Greece, Bavaria, Siberia, Hungary, Spain, Persia, Burgundy, Troglodyte Arabia, Picardy, Bosnia, Jutland, Malta, Portugal, the Himilayas, Central America, Zimbabwe, Lithuania, Poland, Caucasus, Bulgaria, Jordan, and Nubia (Sudan).

The treatise has relevance for other humanities fields as well. Scholars who study European courts or Italian politics will appreciate its bounty of new and unexpected information on the seventeenth-century Medici court and its connections to courts throughout Europe, particularly through its female members. Historians interested in early globalism, exploration, or the circulation of international news will be able to appraise the range of knowledge available in Florence about societies around the globe. For historians of Catholicism, the treatise offers insights into the complexities of the Church’s position on women’s role in secular society, and on how women should be educated.

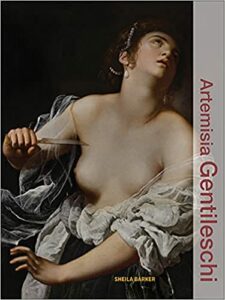

Of the many thousands of pages comprising Bronzini’s immense work, only a few hundred have been read by modern scholars, and most of those pages are in tome 2 of volume 1525. Scholars of music have focused on this tome because of the biographical information it provides for 64 different female musicians and composers. In the case of just one of those, the 17th-century composer Francesca Caccini, this tome provides such abundant and significant information that it served as the basis of Suzanne Cusick’s award-winning book, Francesca Caccini at the Medici Court, Music and the Circulation of Power (2009). This same tome contains descriptions not only of musicians but also of 40 female painters, sculptors, and embroiderers. Most of the artists Bronzini discusses are Italian, but there are also three Spanish artists (María de Jesús Torres, Isabella Sánchez Coello, and Francisca de Jesús), a French painter named Margeurite Bahuche, and, treated in a collective vignette, the women artists of Ming China. As in the case of Caccini, Bronzini was acquainted with several of the artists he wrote about (Lavinia Fontana, Arcangela Paladini, Artemisia Gentileschi, and Giovanna Garzoni) and he had personally seen the artworks of several others (Plautilla Nelli, Diana Scultori, and unnamed Chinese women artists). As Barker’s recent scholarship, Bronzini’s unpublished text provides the earliest biographies ever written for both Giovanna Garzoni and Artemisia Gentileschi.

THE PEOPLE BEHIND THE DIGITAL BRONZINI

The Digital Bronzini Project was initiated by Sheila Barker. Since the summer of 2021, the digitization of the manuscript has been carried out by numerous volunteers. Those who have donated time, effort, and expertise to the project include Judith Weston, Katherine Rabogliatti, Lucia Garofalo, Madison Clyburn, Georgina Rowley, Sophie Jones, Kaylee Kelley, and Quinn Halprin. We thank the staff of the Sala dei Manoscritti at the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze for permitting us to carry out this work and offering kind assistance.

Currently the Digital Bronzini is overseen by a committee that includes Sheila Barker (MAP / University of Pennsylvania), Sheila ffolliott (MAP), Elizabeth Fama (MAP), Sara Mansutti (Transkribus), Katherine Rabogliatti (Syracuse University), Georgina Rowley (University of East Anglia), Carin Zwilling (University of Sao Paulo), Claudius Schettino (Philobiblion), Oded Zrachia (Tel Aviv University), and Nicholas Herman (Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies, University of Pennsylvania).